Advertising campaigns may have a short run or a long life but not many of them outlive the company they once promoted. Even fewer endure to become historical landmarks in their own right. At some point, people walk under, over, or past them without ever knowing why they are there, where they came from, or what company created them.

Boston has one such landmark in its famous Steaming Kettle. But why?

Boston has one such landmark in its famous Steaming Kettle. But why?

The giant kettle has puffed away in downtown Boston for 148 years. In that time, the city has moved it from one location to another around the old Scollay Square neighborhood. It has survived through changes of address and urban renewal.

The buildings that held the golden pot have come and gone, including the original shop, but the Steaming Kettle remains.

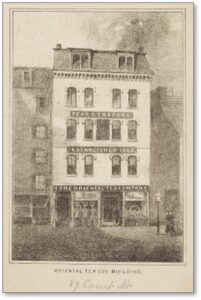

The Oriental Tea Company

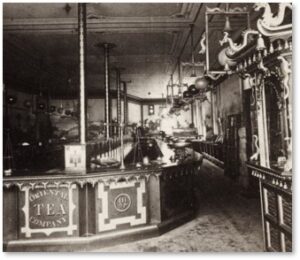

The giant brass kettle, gilded with gold leaf, was created to advertise the Oriental Tea Company, founded in 1868 and located at 85, 87 and 89 Court Street. At the time, the oversized pot had two purposes.

Like any advertising sign, it marked the company‘s location and promoted its products. It also told Boston’s burgeoning immigrant population where to shop. These new residents came to Boston from many different countries and spoke a wide variety of languages written in different alphabets, including Cyrillic, Chinese, and Hebrew. Many spoke no English.

As in Europe, shopkeepers told them what they had for sale by hanging signs that represented the goods inside to guide the illiterate. Anyone who saw the kettle would know they had reached the city’s largest tea shop.

Who Made the Kettle?

A company called Hicks and Badger, Boston’s largest coppersmiths, manufactured the trademark. The kettle contains almost as many facts as tea. In a kitchen, however, it would never have contained tea at all. One heats the water in a kettle, and then pours it on top of loose tea in a teapot. If one uses a tea bag, well, visit the Salada Tea Doors on Stuart Street to see how tea is grown and shipped.

Bostonians take a proprietary attitude toward places and objects that become almost like fellow citizens.

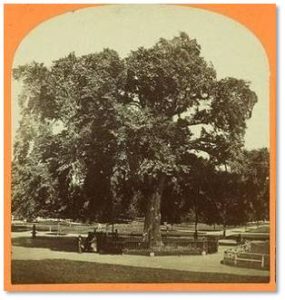

The Great Elm on Boston Common served as a popular gathering place for almost 250 years and was mourned by all when it fell in an 1876 nor’easter. Fenway’s Citgo sign has survived several threats and is featured on shirts, hats, and other Boston / Red Sox gear. The Make Way for Ducklings statues in the Public Garden don their own wardrobes to mark seasons, holidays, and sporting events.

Steam turned the kettle from an ordinary advertisement to today’s tourist attraction. A mechanism in the kettle makes the steam and delivers it via a pipe to the spout, where it bubbles into the air. The steam is especially visible—and welcome—on cold winter days. That innovative piece of engineering endeared the Steaming Kettle to Boston’s residents and probably saved it from hitting the scrap-metal heap long ago.

How Big is the Steaming Kettle?

The man who envisioned the kettle as advertisement had marketing chops worthy of a Madison Avenue agency. Not only did he make the thing itself a beloved landmark, but he also used it to create additional visibility for the Oriental Tea Company.

In 1875, he ran a contest asking the public to guess how much liquid the copper pot could hold. Before the actual event took place, however, our crafty marketer generated more interest with yet another stunt. He hid eight boys and one tall man inside the kettle and they emerged one at a time.

The city’s Sealer of Weights and Measures officially checked each measure as it was poured in. A crowd of 10,000 people filled old Scollay Square to watch and submitted 13,000 guesses. A judge observed the process to ensure fairness and our savvy marketer had a blackboard updated after each measure for the hour it took to fill the kettle.

Think of that: he persuaded two important city officials to spend their time supporting his totally fictitious marketing event.

Calling the Measurement

You can almost hear one of today’s broadcasters commenting after every pour. Folks didn’t have radio in 1873, of course, much less television. Still, I can hear the excitement rising from the crowd as the measurement grew closer to their guess, along with the groans of those who had underestimated the kettle’s capacity.

The crowd cheered when, at 1:05 pm, the official announced the total and eight of the closest guesses were declared winners. The steaming kettle holds:

226 gallons,

2 quarts,

1 pint, and

3 gills

The winners received one-eighth of a chest of tea or about five pounds of tea each. The total volume is now painted on the side of the kettle.

The Tourist Attraction

What began as the Oriental Tea Company’s advertising sign and a publicity gimmick cemented the Steaming Kettle as a Boston tourist attraction. It helps that it hangs today above a Starbuck’s at the corner of Court Street and Tremont Street—only a couple of blocks from the city’s well-traveled Freedom Trail.

The Oriental Tea Company’s shop fell to urban renewal in the sixties and the Government Center T stop replaced it. The Starbucks that currently holds the Steaming Kettle occupies the space that was once the Court Street Tavern. In Sears Crescent, the building that curves along one side of Government Center, just downhill from Starbucks the Phoenix Coffee Mills store reinforced the coffee-tea connection.

The Steaming Kettle appears in every guidebook and map of the city. It has its own entry in Atlas Obscura and is listed on websites like WhereTraveler. It’s famous.

But what about our marvelous marketer—the man who created the enduring landmark? His name has been lost to history. I, for one, think he belongs in the Marketing Hall of Fame.

I know that Shem Drowne made the grasshopper weathervane on Faneuil Hall.

Naomi: I was confused by that, too, as I had learned the same thing. That Shem Drowne, who lived from lived from 1683 to 1774, created the copper weathervane for Quincy Market in 1742. But Quincy Market was built from 1824 to 1826, long after his death. The dates just don’t match. I went through multiple books of Boston history to research this, expecting to find that Drowne had made the grasshopper for another building but they all state that he made it for a market that wouldn’t exist for 82 years.

On the off chance that anyone reads this, Shem Drowne created the grasshopper as a wind vane atop FANEUIL HALL, not Quincy Market. Then the dates work.