“Puddingstone, also known as either pudding stone or plum-pudding stone, is a popular name applied to a conglomerate that consists of distinctly rounded pebbles whose colors contrast sharply with the color of the finer-grained, often sandy, matrix or cement surrounding them. The rounded pebbles and the sharp contrast in color gives this type of conglomerate the appearance of a raisin or Christmas pudding.”

A Rock is a Rock is a Rock

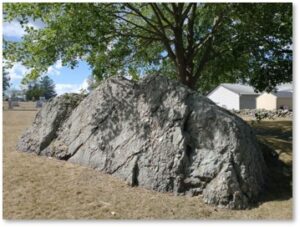

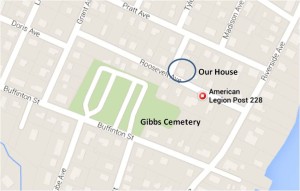

When I was a kid growing up in Somerset, MA, we neighborhood kids used to play in a small cemetery located across the street from my house. My sister and I would get a running start and race up an enormous boulder that lay at cemetery’s east end. Gibbs Cemetery, mostly empty at that end, resembled a lawn with a dirt road around it and boulder in the middle.

We didn’t think much about what kind of stone that boulder was made of. To most kids, a rock is a rock is a rock. We liked the size.

A Local Stone

In college, however, I took a science course that included some basic geology. That’s when I learned our “cemetery rock” was made of something called puddingstone, or Roxbury Conglomerate. The professor noted that this was a local stone not found much outside of the Boston area.

I sat up. I recognized that stone because I had spent a lot of time sitting and climbing on it. (I can still visualize the top of the Gibbs Cemetery boulder in detail.) When I commented that you could find puddingstone as far south as Somerset, the professor was surprised.

We were both right and wrong. The boulder is probably not Roxbury Conglomerate, although is a puddingstone. And the glaciers dispersed conglomerates more widely than the Professor thought.

Underlying Massachusetts

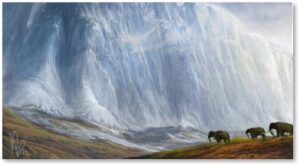

Conglomerate is a type of sedimentary rock formed millions of years ago when the glaciers compressed silt that had smaller rocks and pebbles, called clasts, embedded within it.

Although sedimentary conglomerates can be found all over the world, Roxbury Conglomerate is unique in that it contains Dedham Granite and volcanic rock from the ancient underlying Mattapan Volcanic Complex.

The Boston Basin

In her marvelous folio book “The Atlas of Boston History,” Nancy Seasholes describes the formation of the Boston Basin:

“At the bottom of the basin are two types of bedrock: a shale called Cambridge Argillite, in the northern portion and a conglomerate—stones cemented together in a matrix of clay and sand—called Roxbury Conglomerate in the southern. … There are several types of the conglomerate—one is sandy colored with small stones; another is darker with large cobbles. “

Now, I find this interesting because what I remember of the Gibbs Cemetery boulder is that it had a dark matrix like the Cambridge Argillite but with small pebbles of milky quartz embedded in it. It made so great a contrast, you could see white lines where the quartz pebbles had settled on the bottom.

How Puddingstone Was Made

Oliver Wendell Holmes, who gave us so many memorable words, phrases, bon mots, and poems, popularized the name puddingstone in a poem. Dr. Holmes wrote about the children of giants who got into a food fight when they didn’t like their pudding:

“They flung it over the Roxbury hills,

They flung it over the plain,

And all over Milton and Dorchester too

Great lumps of pudding the giants threw;

They tumbled as thick as rain.

Giant and mammoth have passed away,

For ages have floated by;

The suet is hard as marrowbone,

And every plum is turned to stone,

But there the puddings lie.”

One giant child with a particularly good throwing arm flung his pudding as far south as Somerset. In fact, Robert M. Thorson says in his book, “Exploring Stone Walls: A Field Guide to New England’s Stone Walls” that, “…this rock type is particularly common on the bedrock headlands in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, and in the Boston area.”

Using the Puddingstone

As the glaciers — the last being the Laurentide Ice Sheet — made and scattered Roxbury Conglomerate all around the Boston area, farmers had to dig it up before they could plant their fields. It thus became a ubiquitous component of the region’s stone walls and building foundations. Sometimes workmen cut and shaped it, while in other places they left it rough.

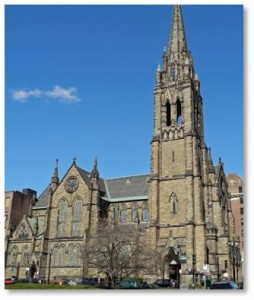

Puddingstone would seem an unlikely building material with its rocks and pebbles sticking out all over the place. In fact, however, it seems tailor-made for New England’s buildings. Dr. Jack Share states:

“Typically, conglomerate is a rather coarse, irregular and somewhat friable material as a building stone, especially in comparison to granite, which later gained prominence in its use in Boston. This can make conglomerate unsuitable for architectural use. However, the firmly-cemented and relatively high compressive strength of the local puddingstone in Boston was the exception. In addition, the stone is impervious to moisture and resistant to New England’s frost and harsh winters. Over time, the rock has not been observed to crack, scale, crush or disintegrate, and the color of the seam-faces remains stable.”

Nancy Seasholes adds that “Because puddingstone resists breaking when frozen, it has been quarried extensively for use in building construction, especially the light-colored variety for many Boston churches.” Because of this, Roxbury Conglomerate has been called “church stone.”

I thought it was used so often because the rock could be found everywhere and was therefore cheap. Thrifty New Englanders typically made the best use of available materials. In this case, however, the available materials also made the best materials.

Puddingstone Points

-

Roxbury Conglomerate underlies so much of Roxbury that it gave its name to the town of Roxbury (or Rocksbury on early maps).

- It was named the state stone of Massachusetts in 1983.

- More than 35 churches in the Boston area were built with puddingstone, including Old South Church, the Brattle Square (First Baptist) Church, the Church of the Covenant, Mission Church and the Cathedral of the Holy Cross

- Puddingstone was used as the base of the memorial for the founder of the Order of the Elks in Mount Hope Cemetery where there are many natural outcroppings

- Cemeteries accumulated puddingstone monuments

- Frederick Law Olmsted often used puddingstone for borders and structures in the parks he designed

- Kevin W. Fitzgerald Park (formerly Puddingstone Park) is a 5.5-acre neighborhood park near Brigham Circle in Boston’s Mission Hill neighborhood. The city built it as part of the redevelopment of a former Puddingstone quarry called the “ledge site.”

As fellow Boston By Foot docent Heather Pence tells us in the City of Boston blog:

“In 1886 a 30-ton Puddingstone boulder was sent from Roxbury to Gettysburg to be used as a monument to the 20th Massachusetts regiment on the Battlefield. The boulder now commemorates 43 Massachusetts soldiers who died or were mortally wounded absorbing the brunt of Pickett’s Charge during the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. The idea for a monument using this boulder came from some of the 20th Massachusetts Regiment soldiers who remembered playing on such boulders when they were children.”

Sound familiar?

Finding Puddingstone

To see puddingstone in construction, go to any of the churches listed above and get right up close to the stone walls. You will see the pebbles and cobbles embedded in the matrix like the raisins, nuts, and currants in a Christmas pudding.

If you want to see the multiple layers of stone that underlie the Boston Basin, go to page 4 of “The Atlas of Boston History.” Ms. Seasholes gives us a beautiful photographic representation of the geologic levels from Cambridge Argillite bedrock on the bottom to historic fill on the top.

To see the real thing in Somerset, head down Roosevelt Avenue and park in front of the American Legion Hall. Walk past the Legion Hall (on your left) and cross the stone wall into the cemetery. You can’t miss that boulder. Or go into the Buffinton Street entrance to Gibbs Cemetery and drive east (downhill) until you see the boulder.

Just don’t try to eat the pudding.