Recent articles in a number of media outlets have predicted the future of work. Opinions from the “experts” differ widely and one has to keep an objective outlook, considering what political position or economic philosophy the author or publication may be promoting. Generally speaking, the ideas fall into several categories:

- Full-time employment is going away. In 10 years, everyone will be juggling several part-time jobs with no steady income, benefits or health care.

- Full-time employment is staying but only for those who have advanced degrees or very specialized training. Everyone else will be juggling several part-time jobs with no steady income, benefits or health care—if they’re lucky.

- Full-time employment is staying but companies can’t find enough employees with good STEM training to fill those jobs. The government needs to open up more H-1B visas so companies have access to qualified candidates.

- Millennial employees prefer the independence and autonomy of being freelance workers and would rather do that than fill a regular job. They are migrating out of the corporate world into doing their own thing.

These are all interesting ideas, even if none of them seems like particularly good news for the American or work force. And this is certainly one of those inflection points in the economy when things may change—whether for better or worse—and never go back to where they were before.

Life on One Salary

Think of the 1950s, when men worked at a full-time job and women stayed home and raised families. My father never made a huge salary but—with careful budgeting—he was able to support a wife and four children on it. A solidly middle-class family, we lived in a house and had a car; we ate well and went on a vacation every year. That all changed in the 1970s when economic malaise and “stagflation” made it impossible to support a family on one income. Wives and mothers went into the workforce by the thousands to supplement their husbands’ salaries. Not only has that dynamic never reversed itself, it is getting worse. Companies are now in a race to the bottom to see how low they can drive wages and how many full-time positions they can eliminate. Sometimes they replace employees with part-time workers, temporary workers, and consultants, while other times they leave the positions unfilled. The money they save isn’t re-invested in the company, it goes into outrageous CEO salaries and executive perks.

Not only has that dynamic never reversed itself, it is getting worse. Companies are now in a race to the bottom to see how low they can drive wages and how many full-time positions they can eliminate. Sometimes they replace employees with part-time workers, temporary workers, and consultants, while other times they leave the positions unfilled. The money they save isn’t re-invested in the company, it goes into outrageous CEO salaries and executive perks.

Eventually, the country’s workforce will hit bottom. What happens then? The economy sloooowwws even further.

Stagnant Wages

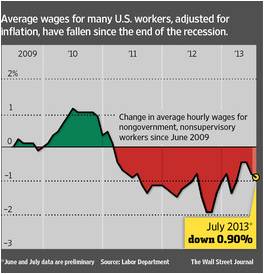

As Neil Shah reported in Monday’s @WSJ, “Stagnant Wages Crimping Economic Growth,” the salaries of people fortunate enough to have jobs are not keeping up with inflation and that erodes consumer spending. It should not surprise anyone with the brains God gave a tractor that when you eliminate jobs, pay your remaining employees less, fill in with temp help that receives no benefits, and off-shore your manufacturing to an Asian country, eventually the American market for your products or services will shrink. Then it will dry up.

As Mr. Shah points out, “. . . it is harder for them to make purchases ranging from refrigerators to restaurant meals that account for most of the nation’s economic growth.” Well, duh. The bottom line here is simple: if you don’t invest in your own country, eventually the population of that country will lose the ability to buy your products. Companies that want to sell their products in the United States might want to re-think their employment and manufacturing strategies.

Which brings me to business fads. I’m wondering whether the current employment situation just reflects the latest one. We have seen these fads come and go over the years as the “best and brightest” of our business leaders come up with new ways to loot the economy, the markets, or their own companies for their personal wealth and glory.

The Downsizing Fad

The current downsizing fad reminds me of the merger/acquisition, or “debt is good,” fad of the seventies. Back then, CEOs burdened their companies, or the ones they acquired, with huge amounts of debt, laid off tens of thousands of employees and watched the stock value rise as Wall Street applauded their audacity. That fad lasted until someone looked around and noticed that the emperor had no clothes. Someone, I forget who exactly, popped his head up and announced that no company had ever downsized its way to profitability. This piece of common sense was hailed as a brilliant insight—which tell us something about how smart business executives really are.

Darden Restaurants just learned this lesson in their Red Lobster restaurants, as reported by Brad Tuttle in @theTimemagazine. The article is entitled, “Efficiency Backlash: Companies Learn Too Much Downsizing Can Hurt the Bottom Line.” As Mr. Tuttle reports, “In July 2012, the restaurant chain, owned by Orlando-based Darden Restaurants, eliminated the busboy position, demoted many waiters to lower-paid status as ‘service assistants’ and forced the remaining full-fledged servers to increase the number of tables they handled from three to four.” This was supposed to improve efficiency. Well, maybe it would have if their customers were robots who didn’t mind waiting a long time for their food. But insulting your employees, making their jobs more difficult, and forcing them to work harder for less doesn’t make them really eager to give customers a “great guest experience.” Having learned this the hard way, Darden has reversed the policy.

Other smarter, companies, like Costco and Trader Joe’s, decided that staffing their stores with employees who earn a good salary and are happy with their jobs is a good policy. It leads to employee satisfaction and a better customer experience.Will others learn the hard way, follow good examples, or figure it out on their own? Who knows? The only thing that will turn this dismal picture around is a robust economy in which employers must compete for qualified employees, which drives up wages, and gives workers bargaining power.

My Efficiency Backlash

In the meantime, I conduct my own efficiency backlash in four small ways. It may not amount to much in the greater scheme of things but it’s what I can do on my own.

- I don’t ever use self-checkout. Ever. Not at Home Depot, the supermarket, or any other retail location. Self-checkout forces the customer to do the work employees used to do before they got laid off. Worse, we don’t even get a discount for ringing up our own items, so the company saves money but we don’t. Essentially, the customer provides free labor. Why would I do this? Why would anyone do this? If I’m forced to use self-checkout, I leave the store.

- If I walk around a store and can’t find a sales representative to help me, or even one to take my money, I leave. Obviously, the company doesn’t want me there or they would make it easier for me to buy their products.

- If I call to make a purchase, and the voice on the other end is clearly located in another country, I stop the process and hang up. Why do I want to reward companies that send their jobs overseas?

- If I have a choice between buying a product made in China or some other low-wage country and one made in the United States, I buy the one made in the U.S., even if it costs more or the other one seems nicer. That depends, of course, on such a choice even existing.

Do you have your own ways of protesting? If so, please comment. I would love to hear your ideas.