Monday Author: Susanne Skinner

The idea of celebrating and honoring the dead appeals to me. It’s not an American tradition; but it has religious cousins in the Catholic/Christian tradition of All Souls Day, or as I remember it—a High Holy Day of Obligation that found me sitting in a church pew wishing I could be anyplace else.

All Souls Day commemorates the souls of the Faithfully Departed who are in Purgatory, waiting to be absolved of their sins so they can enter Heaven. This is not to be confused with All Saints Day, which is the day before All Souls Day and celebrates those who are already in Heaven. Both of those come after Halloween. When you are a kid that means a fun day followed by two church days.

All Souls Day commemorates the souls of the Faithfully Departed who are in Purgatory, waiting to be absolved of their sins so they can enter Heaven. This is not to be confused with All Saints Day, which is the day before All Souls Day and celebrates those who are already in Heaven. Both of those come after Halloween. When you are a kid that means a fun day followed by two church days.

What if you departed un-faithfully—are you still commemorated? Why do we only think of them one day a year? What exactly is the purpose of Purgatory? How long does it take to go from A Soul to A Saint? These questions went through my 10-year-old mind and are still in my much older mind today.

If we’re going to limit remembering our departed loved ones to a few days, I much prefer the Day of the Dead, or Día de los Muertos, because it really is a celebration. It involves food, and it assumes our loved ones are already in The Good Place.

Mesoamerican Origins

The Mesoamerican civilization is the amalgamation of native Mexican and Central America cultures and religious beliefs that developed before the 16th century. Their belief in the afterlife dates back over 5000 years.

Archaeological sites in Mexico reveal the elaborate methods in which people were buried during that time, indicating not just a belief in the afterlife but in ritual practices related to death.Tombs were often constructed beneath the homes where the person had lived, so deceased loved ones remained close to their living family.

These tribes shared a belief that death was a creative moment in the cosmic process. Mourning the dead was only part of the ritual. To them, the cosmos and the human body were supernatural connections that were all encompassing, so life could literally emerge from the world of the dead.

Merging Traditions in the Day of the Dead

When the Spaniards arrived in the sixteenth century, they introduced the Catholic faith to the indigenous people of Mesoamerica and worked hard to eradicate their native beliefs. They were somewhat successful, meaning Catholic teachings and native beliefs intermingled to create new traditions.

The festival celebrating deceased ancestors was moved to coincide with the Catholic holidays of All Saints Day (November 1st) and All Souls Day (November 2nd), and although it is considered a Catholic holiday, it still has rituals that were carried over from the pre-Hispanic celebrations.

The festival celebrating deceased ancestors was moved to coincide with the Catholic holidays of All Saints Day (November 1st) and All Souls Day (November 2nd), and although it is considered a Catholic holiday, it still has rituals that were carried over from the pre-Hispanic celebrations.

In Mexico, Day of the Dead is festive. It is a celebration lasting several days that incorporates ancient beliefs honoring loved ones and the mobius loop of life and death in the cosmic journey.

It begins when the gates of heaven open at midnight on October 31 and the spirits of all deceased children reunite with their families for 24 hours. On November 2, the spirits of the adults come down to enjoy the festivities prepared in their honor.

Celebrations include graveside vigils with altars honoring the deceased’s life. Some families construct altars in their homes, decorating them with Mexican marigolds, candles, skull iconography, and even personal items and offerings of favorite foods. Toys are left for the children.

The Symbolism of Food

A very important part of this celebration is food, and I am down with any holiday that involves cooking and baking.

Día de los Muertos has it all. The food is prepared and eaten by the living and offered to the spirits of their ancestors. Traditional Día de los Muertos foods include pan de muerto, pickled vegetable salad, thick hot chocolate, and sugar skulls

Día de los Muertos has it all. The food is prepared and eaten by the living and offered to the spirits of their ancestors. Traditional Día de los Muertos foods include pan de muerto, pickled vegetable salad, thick hot chocolate, and sugar skulls

Pan de muerto is a traditional yeasted sweet bread flavored with orange or anise essence and dusted with sugar. Every bakery in Mexico prepares this for the celebration. It is one of the special offerings on the altar, believing the returning spirits are nourished by the essence of the bread. The shape of the bread is full of symbolism; shaped like a cross to represent the bones of the dead. A ball is placed on top of the loaf, symbolizing tears for the dead or perhaps a heart.

Fiambre is a no-rules pickled vegetable salad with many variations. Prepared several days before serving, it marinates in a blend of vinegar, oil and seasonings. Recipes are handed down within families and some even include meat.

Spiced hot chocolate is a culinary revelation that removes packaged hot cocoa mixes from your mind forever! This recipe is made with semi-sweet chocolate and coconut milk with a bit of heat from the chili. You can substitute the chocolate with a high-quality cocoa powder.

If you don’t want to go through the steps of a recipe you can still have something authentic by purchasing Ibarra chocolate. Just add it to milk at heat it up.

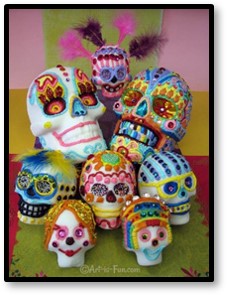

Sugar Skulls are one of the most recognized symbols of the Mexican Day of the Dead. They are purchased or made by families to place on the altar, often writing the name of their loved ones on the skill forehead. Sugar skulls are sometimes eaten, but their main purpose is to adorn the altars and tombs with a sugary treat for the visiting spirits.

Death Is Not the End

In Mexico, death is not the end, it’s just a new beginning. Día de los Muertos is more of a cultural holiday than a religious one. It is reflective, celebrating the memories of loved ones through cooking, art, music and traditions embodying the belief that happy spirits provide protection, good luck and wisdom to their families.

In Mexico, death is not the end, it’s just a new beginning. Día de los Muertos is more of a cultural holiday than a religious one. It is reflective, celebrating the memories of loved ones through cooking, art, music and traditions embodying the belief that happy spirits provide protection, good luck and wisdom to their families.