Yesterday we went to see “Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry” that runs until February at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. This outstanding exhibition pulls together many of Johannes Vermeer’s paintings and puts them in context with the work of his contemporaries and rivals.

Genre Paintings and the High Life

The catalog describes genre paintings as, “. . . scenes of daily life, from the third quarter of the seventeenth century. Made during a time of unparalleled innovation and prosperity these exquisite portrayals of refined Dutch society—elegant men and women writing letters, playing music and tending to their daily rituals—present a genteel world that is extraordinarily appealing.”

These “High Life” works show Dutch citizens, most often women, going about their everyday activities inside the house. In genre paintings, men often visit or intrude upon the women’s space.

These “High Life” works show Dutch citizens, most often women, going about their everyday activities inside the house. In genre paintings, men often visit or intrude upon the women’s space.

The National Gallery has grouped the paintings not by date, artist, or style, but by the activities of the subjects. Thus, we get to compare the approach of people performing the same task by Johannes Vermeer, Gabriel Metsu and Gerard ter Borch, Caspar Netscher, and Gerritt Dou, among others, all right next to one another. See how they differ in brush strokes, treatment of fabric, setting, and—above all—light, by just turning your head.

Vermeer’s Light

Because light is what distinguishes the paintings of Johannes Vermeer from all the others. I recommend following my standard exhibition system. I look at all the paintings in a room up close, one by one, and then I sit in the middle of the room and just absorb the works for a few moments. Art that looks vibrant up close because of the colors or the composition can seem flat when viewed from a distance. But Vermeer’s paintings always leap out because of his vibrant, glowing treatment of light.

The movie “Tim’s Vermeer” makes an interesting case that he achieved this vibrant light by using an optical device called a camera obscura that allowed him to copy tones directly on canvas instead of interpreting them visually.

The movie “Tim’s Vermeer” makes an interesting case that he achieved this vibrant light by using an optical device called a camera obscura that allowed him to copy tones directly on canvas instead of interpreting them visually.

Academic Joshua Gans disputes this theory based on his attempts to replicate it, while others such as website howtotalkaboutarthistory.com, think that it’s an interesting approach.

I have no opinion except to wonder why so many of his genre paintings are set in the same corner of the same room with light pouring in from the same window. Vermeer moves around furniture, draperies and objects on the wall but, still, it’s a lot of attention to put into one place without a good reason.

Recurring People and Props

Of course, we become very well acquainted with other recurring people and objects, too. Gerard ter Borch posed his half-sister, Gesina, in many of his paintings and used the same drapery or table covering so many times I wondered why he didn’t get tired of painting it. Gesina appears to have posed for other genre artists along with elaborate red-and-blue table coverings of their own. Is this art imitating art?

Recurring themes include writing, reading and sealing letters, getting dressed for the day, holding a parrot, playing musical instruments of various types and working in the kitchen.

Bringing Them Together

The curators have done an outstanding job of assembling paintings from museums and private collections all over the world.

Note: I always read the cards that tell me who loaned the paintings in any exhibition and it amazes me how many works by Old Masters remain in private hands.

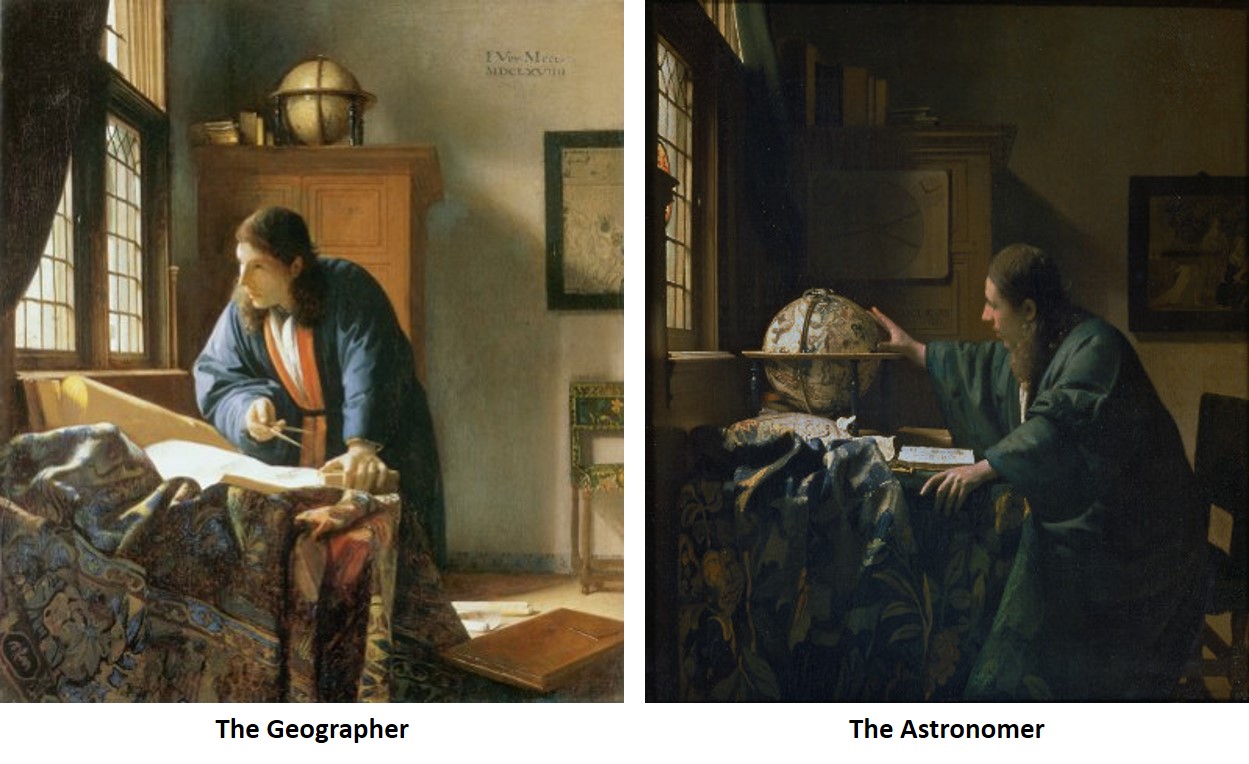

This exhibition offers the rare opportunity to see Vermeer’s “The Astronomer” and “The Geographer” side by side, as the former resides in the Louvre Museum in Paris and the latter calls Frankfurt’s Städelsches Kunstinstitut home. That makes the show worth traveling to see.

I have viewed many of the 18 attributed paintings Vermeer completed in his lifetime, either in their “home” museum or in exhibits like this one at the National Gallery. I even saw “The Concert” in Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum before it was stolen in the1990 Gardner Heist. (No one but the thieves have seen it since.)

I hope to fill in the rest over time. “The Music Lesson,” subject of the movie “Tim’s Vermeer” remains out of reach in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. I haven’t been invited.

The American People’s Museum

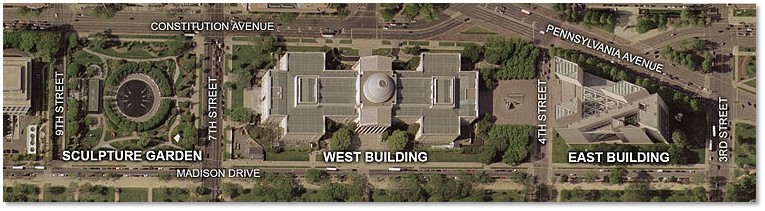

But the National Gallery in Washington D.C. is the American people’s art museum. We pay for it with our taxes and it charges no admission fee and no fee to see “Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting.” If you have never seen this amazing museum, you owe to yourself to visit.

“Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting” closes on January 21. It’s moving to Paris and then Dublin. If you love art — or even if you have never thought about art, don’t miss it. The exhibit is located at the east end of the West Building. Try to visit on a weekday and get there early. The National Gallery opens at 10:00 a.m.