Every sports fan in Boston—and in many other parts of the country—knows that Causeway Street is the address of the “Bawstin Gahdin.” Currently the TD Garden, this arena houses the Boston Celtics and the Boston Bruins, as well as rock concerts and other big events.

Now, a causeway is defined as, “a road or railway on top an embankment usually across a broad body of water or wetland.” So, where’s the embankment around the TD Garden? Where’s the wetland? Why is this broad thoroughfare called Causeway Street if there’s no water, embankment or causeway?

Back to the Shawmut Peninsula

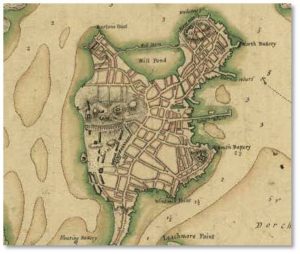

Aha! To find the reason we have get into the Wayback Machine and go way, way, way back in Boston history. All the way back, in fact, to the Shawmut Peninsula that originally made up the entirety of Boston’s available land—only 789 acres.

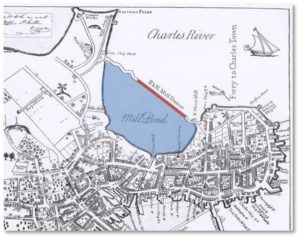

In between the North End and the West End promontories of the peninsula lay the Mill Pond, a marshy cove that filled at high tide and drained out at low tide.

In 1643, Boston’s Town Fathers granted the entire cove to a group of shareholders with the mandate that they build one or more grist mills and maintain them. The town used this typical “linkage grant,” to get public works built at private expense. (Similar to what is supposed to happen with public parks in the Seaport today.)

Damming the Mill Pond

Although it took them longer than anticipated, the new proprietors connected the ends of a long narrow island that existed at the mouth of the cove to create a dam. As part of their agreement with the city, they also built a ten-foot gate through which boats could enter the cove. In a third part of the project, the proprietors dug a mill creek through Boston Neck between the Mill Pond and the Town Cove. This allowed boats to pass freely into Boston Harbor.

Water from the Charles River poured through the floodgates and into the Mill Pond at high tide, as well as from the Town Cove through the Mill Creek.

When it flowed back out again at ebb tide, it powered tidal grist mills that surrounded the pond. It also flushed out anything that had been thrown, discarded, or dropped into the Mill Pond.

The Environmental Impact

Back then, no one conceived of an Environmental Impact Statement, however, and anyone wanting to protect wetlands would have been laughed out of the room. The citizens saw wetlands as just mud flats and marshes to be filled and developed. This ongoing land making created space for a burgeoning population. In the 20 years from 1790 to 1810, the city’s population shot up from 18,320 to 33,787.

Although the proprietors dredged the Mill Pond periodically to keep it navigable, they failed to maintain the mills, as their contract required them to do. By the latter part of the 19th century, the mills had deteriorated, becoming dilapidated and mostly disused.

When a new group of owners took over the enterprise in 1800, they shut the floodgates at the western end of the dam, thus stopping the inflow of water from high tide. Like many bodies of water in this period, the Mill Pond served as an easy disposal mechanism for filth, rubbish, dead animals and privy runoff. Without the tides to clean and refresh it, this noxious debris accumulated in the Mill Pond and the connecting creek also silted up, becoming shallow.

This state of affairs did not bother the new owners, however, because their goal was not industry but speculation—to sell lots on the edge of the Mill Pond and eventually lay streets across it. This scheme had the dual advantage of providing more land for the growing population while removing a stinking nuisance and health hazard.

Filling the Mill Pond

In 1807 the proprietors petitioned the city to allow them to fill in the Mill Pond and in September of that year the city allowed the Boston Mill Corporation to do so. The new plots of land would be used to house working-class citizens.

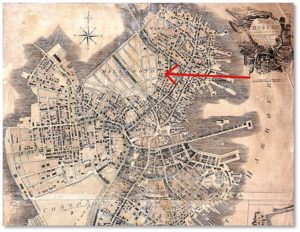

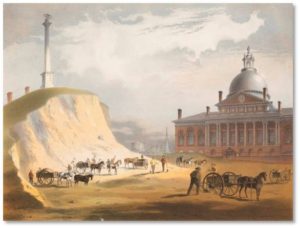

In the city’s first major land-making project, the BMC filled in the Mill Pond with dirt and gravel taken from the tops of Beacon Hill and Copp’s Hill. This work was done manually by laborers with picks and shovels and carts—slow work for such a large project. So, it comes as no surprise that the filling of the Mill Pond took 21 years to complete, from 1807 to 1828.

When finished, this project added 10% more land, 50 acres, to the Shawmut Peninsula.

The Bulfinch Triangle

Charles Bulfinch, architect of many Boston buildings and head of the Town Selectmen, laid out the streets and lots on that new land in 1808. Without a street grid to match on either side Mr. Bulfinch anchored his plans on the causeway and dam. This, combined with the shape of the Mill Pond, created an area known as the Bulfinch Triangle, which is still clearly visible on a street map of Boston today.

Thus, the Mill Cove became the Mill Pond, which turned into the Bulfinch Triangle. Causeway Street stretches across the exact location of the original dam–an actual causeway. It marked the northern boundary of the Triangle with the Charles River on the other side. The two sides of the triangle are bordered by Merrimac Street on the west and North Washington Street on the east. Market Street truncates the point of the triangle.

Causeway Street Today

Today, Causeway Street is a land-locked thoroughfare two blocks from the Charles River at its closest point and much further away to the west, thanks to more land making.

The next time you go to a game at “The Gahdin” or fume at the traffic on Causeway Street, remember that this street really was once a causeway with water on both sides.

Look toward downtown Boston and you‘ll be looking across the Bulfinch Triangle. This area is newly trendy, with luxury residential buildings just completed. I suspect that most of the tenants have no idea they are living atop made land that came from Beacon Hill and Copp’s Hill—and before that their neighborhood was a tidal cove.